Ecological Democracy and the Big Cities: Imagining an Urban Future

Cities are organisms composed not only of brick, glass, and steel but of ideas, dreams, and democratic desires. When we speak of ecological democracy, we embrace an expansive notion—one where democratic practice and ecological awareness coexist, reinforcing each other.

Key Insights

Essential takeaways from this chronicle

Ecological democracy envisages urban governance driven by inclusion, equity, and sustainable stewardship

Point 1 of 6Urban green spaces represent democratic potentialities that transcend socio-economic divides

Point 2 of 6Participatory ecological governance empowers residents to shape their urban environments

Point 3 of 6Ecological rights must be recognized as fundamental democratic rights for all urban residents

Point 4 of 6True sustainability requires democratic engagement rather than technocratic management

Point 5 of 6Ecological citizenship cultivates shared responsibility toward urban ecosystems

Point 6 of 6

Ecological Democracy and the Big Cities: Imagining an Urban Future

I. The Urban Condition and Democratic Ecology

The framework of ecological democracy in urban governance

The framework of ecological democracy in urban governance

Every city possesses its own ecology, an invisible yet potent force interwoven through its streets and parks, rivers, and buildings. This ecology, however, remains constrained by power imbalances and limited civic engagement. Large cities like Tokyo, New York, and Mumbai offer instructive contrasts. Tokyo, though vast and dense, features robust participatory processes enabling community influence over ecological planning, from recycling programs to green space allocation. New York, by contrast, oscillates between progressive ecological policies in affluent neighborhoods and neglect in poorer districts, reflecting broader democratic inequalities.

Mumbai epitomizes ecological democracy's necessity through stark contradictions—rapid urbanization challenges democratic ideals, exposing ecological vulnerabilities like flooding and pollution. Here, democracy must assert itself ecologically, emphasizing collective voice, equitable access to resources, and participatory decision-making.

Ecological democracy envisages urban governance driven by the inclusion, equity, and sustainable stewardship of natural resources. It questions who holds power over ecological decisions in urban spaces and insists upon broad participation in shaping the urban ecological landscape.

II. Urban Nature and Democratic Spaces

Public parks and gardens as spaces of democratic potential

Public parks and gardens as spaces of democratic potential

The democratic value of urban green spaces emerges clearly when examining parks and gardens as democratic arenas. These spaces represent more than mere urban amenities—they embody democratic potentialities, spaces open to all, transcending socio-economic divides. Central Park in New York, Hyde Park in London, and Parque Ibirapuera in São Paulo exemplify democratic ecological spaces, yet reveal inequalities too. These iconic green spaces risk becoming commodities, alienating underprivileged citizens through gentrification and commercialization. Ecological democracy demands that urban nature remains accessible, inclusive, and democratically governed.

The transformation of these spaces from public commons to curated experiences reflects broader trends in urban governance. When green spaces become revenue-generating assets rather than democratic forums, they lose their capacity to serve as equalizing forces in urban society. Ecological democracy insists that these spaces remain fundamentally public, shaped by the communities they serve rather than the markets they might attract.

III. Ecological Governance and Citizen Participation

Community participation in ecological planning decisions

Community participation in ecological planning decisions

Consider governance as an ecological metaphor—diverse stakeholders coexist and negotiate, shaping shared urban ecosystems. Cities such as Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Barcelona are pioneering forms of participatory ecological governance. Amsterdam's participatory budgeting empowers residents directly to allocate funding for ecological projects, democratizing resource control. Copenhagen's democratic assemblies engage citizens in planning sustainable transport infrastructure, ensuring ecological policies align with local aspirations. Barcelona's "superblocks" initiative reclaims streets from cars through community participation, transforming urban ecology democratically.

These examples demonstrate the possibilities when ecological democracy becomes tangible, shaping cities collaboratively, ensuring urban environments reflect collective, democratic aspirations. The key innovation in these cities is not technological but institutional—creating structures that enable meaningful participation in ecological decision-making.

Amsterdam's approach to participatory budgeting for ecological projects provides a particularly instructive example. By giving residents direct control over a portion of the city's budget for environmental initiatives, the city has created a mechanism for democratic ecological governance that goes beyond consultation to actual decision-making power. This model has been replicated in various forms across Europe and Latin America, demonstrating the scalability of ecological democratic practices.

IV. Ecological Rights as Democratic Rights

Ecological democracy recognizes ecological rights as fundamental democratic rights. Clean air, potable water, and safe public spaces are not privileges but rights democratically guaranteed to all urban residents. This vision emerges clearly in cities battling ecological injustices: Flint, Michigan, with its water crisis, Delhi's hazardous air quality, and Rio de Janeiro's informal settlements lacking basic sanitation. Ecological democracy insists these rights are inviolable and democratic mechanisms must enforce them. Civic engagement, collective action, and ecological activism thus become essential democratic tools.

The case of Flint, Michigan, illustrates the failure of democratic systems to protect ecological rights. When the city's water supply was contaminated with lead, residents were systematically ignored by government officials at multiple levels. The crisis revealed not just a failure of infrastructure but a failure of democratic accountability. Ecological democracy requires mechanisms that ensure ecological rights cannot be compromised for economic or political expediency.

Delhi's air quality crisis presents a different challenge—one of scale and complexity. The city's air pollution affects millions of residents, yet the sources of pollution are diffuse and often located outside the city's jurisdiction. Ecological democracy in such contexts requires regional cooperation and the recognition that ecological rights transcend administrative boundaries.

V. Democracy, Ecology, and Urban Sustainability

Sustainability, a foundational ecological democratic principle, necessitates democratic engagement. Sustainability devoid of democratic participation becomes mere technocratic management, indifferent to human needs and local contexts. Cities achieving true sustainability do so through democratic, participatory processes. Freiburg, Germany, and Curitiba, Brazil, offer pioneering examples. Freiburg's participatory planning integrates ecological sustainability directly into democratic practice, while Curitiba's democratic urban innovations, including accessible public transit and inclusive green policies, underscore ecological democracy's transformative power.

Freiburg's approach to sustainable urban development demonstrates how ecological goals can be achieved through democratic means. The city's extensive public consultation processes ensure that sustainability initiatives reflect community values and priorities. This democratic approach has resulted in high levels of public support for environmental measures, from renewable energy adoption to sustainable transportation policies.

Curitiba's experience with bus rapid transit (BRT) systems illustrates how democratic ecological governance can lead to innovative solutions. The city's BRT system was developed through extensive community consultation and has become a model for sustainable urban transportation worldwide. The system's success demonstrates that ecological solutions are most effective when they emerge from democratic processes rather than being imposed from above.

VI. Ecological Justice and Democratic Inclusion

Ecological democracy demands justice and inclusivity, countering urban ecological inequities. Vulnerable populations—marginalized, economically disadvantaged, historically excluded—face disproportionate ecological harm. Detroit's abandoned neighborhoods, Kolkata's polluted slums, and Johannesburg's environmentally degraded townships exemplify ecological injustice. Democratic ecological governance mandates inclusion and empowerment, ensuring marginalized voices shape ecological policies, transforming urban landscapes equitably and sustainably.

The case of Detroit reveals how economic decline can compound ecological injustice. As the city's population declined and tax base shrank, basic services including environmental protection were cut back, disproportionately affecting remaining residents. Ecological democracy requires mechanisms to ensure that economic challenges do not result in ecological abandonment.

Kolkata's slums face a different form of ecological injustice—one of proximity to environmental hazards without access to environmental benefits. Residents of informal settlements often live near industrial facilities, waste dumps, or polluted waterways while lacking access to clean water, sanitation, or green spaces. Ecological democracy requires addressing these inequities through inclusive planning processes that prioritize the needs of the most vulnerable.

VII. Urban Ecological Citizenship

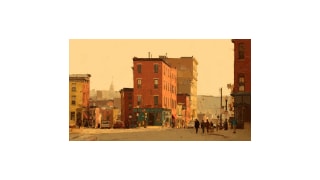

Citizen-led ecological action and community engagement

Citizen-led ecological action and community engagement

Urban ecological democracy cultivates ecological citizenship—a shared responsibility toward urban ecosystems and collective democratic participation. Ecological citizenship empowers individuals, fostering awareness and democratic engagement. Education programs, community initiatives, and ecological awareness campaigns nurture ecological citizens who actively shape urban ecological futures democratically. Helsinki's grassroots environmental groups and Melbourne's community-driven ecological initiatives exemplify ecological citizenship, transforming urban ecology democratically from the grassroots.

Helsinki's approach to ecological citizenship education demonstrates how cities can cultivate democratic ecological awareness. The city's environmental education programs engage residents of all ages in understanding and participating in urban ecological governance. These programs go beyond traditional environmental education to include democratic skills and civic engagement training.

Melbourne's community-driven ecological initiatives show how grassroots organizations can drive ecological democratic change. The city's numerous community gardens, urban farming projects, and environmental advocacy groups demonstrate the power of citizen-led ecological action. These initiatives not only improve the city's ecological health but also strengthen democratic participation and community cohesion.

VIII. Future Visions of Ecological Democracy

Envisioning ecological democracy's urban future means imagining cities governed democratically and ecologically attuned. It means cities characterized by participatory governance, ecological rights, sustainability, ecological justice, and active citizenship. Cities of the future must reject authoritarian ecological models, emphasizing democratic, inclusive, sustainable urban governance.

The cities of the future will need to balance global ecological challenges with local democratic imperatives. Climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion require coordinated action at multiple scales, while democratic governance requires local participation and control. Ecological democracy provides a framework for achieving both goals simultaneously.

Technological innovation will play a role in enabling ecological democracy, but technology alone is insufficient. Digital platforms can facilitate participatory planning and democratic deliberation, but they must be designed to promote inclusion rather than exclusion. The challenge is to use technology to enhance rather than replace democratic ecological governance.

IX. Conclusion: Democratic Ecological Futures

Ecological democracy, far from utopian idealism, represents urgent necessity. Cities worldwide face profound ecological challenges, requiring democratic engagement, inclusion, and participation. Urban ecological democracy must transcend rhetoric, becoming practice, transforming cities democratically and ecologically.

Thus, ecological democracy redefines urban life, embedding ecological consciousness within democratic practice, transforming cities into equitable, inclusive, sustainable habitats. This democratic-ecological synthesis emerges as our collective urban future, demanding profound democratic commitments and ecological awareness, defining the cities we aspire to inhabit.

The path toward ecological democracy is not easy, but it is necessary. It requires reimagining urban governance, redefining citizenship, and rebuilding the relationship between humans and the natural world. It requires recognizing that ecological health and democratic health are inseparable—that we cannot have one without the other.

The cities that embrace ecological democracy will be the cities that thrive in the 21st century. They will be cities where residents have meaningful voice in ecological decisions, where ecological rights are protected for all, and where sustainability emerges from democratic practice rather than technocratic imposition. These cities will serve as models for a new form of urban civilization—one that is both democratic and ecological, both human and natural.

"Ecological Democracy and the Big Cities" is part of Atlas Urbium's ongoing series examining the intersection of democratic governance and urban sustainability. Read more about urban transformation in our essays on smart cities and human experience, community listening and urban planning, and sustainable urban infrastructure.

References:

- Bookchin, M. (1987). "The Rise of Urbanization and the Decline of Citizenship." Sierra Club Books.

- Dryzek, J. S. (2000). "Deliberative Democracy and Beyond: Liberals, Critics, Contestations." Oxford University Press.

- Fainstein, S. (2010). "The Just City." Cornell University Press.

- Healey, P. (1997). "Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies." Macmillan.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). "The Death and Life of Great American Cities." Random House.

- Lefebvre, H. (1996). "Writings on Cities." Blackwell Publishers.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). "Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action." Cambridge University Press.

- Purcell, M. (2008). "Recapturing Democracy: Neoliberalization and the Struggle for Alternative Urban Futures." Routledge.

- Sassen, S. (2011). "Cities in a World Economy." SAGE Publications.

- United Nations Habitat. (2020). "World Cities Report 2020: The Value of Sustainable Urbanization." UN-Habitat.

Continue Reading

More Stories Coming Soon

We're working on more urban chronicles to share